Fingersmith and The Handmaiden:

Rewatching one of my favourite Park Chan-wook movies, brought home the importance of distinguishing the erotic from the pornographic. The heroines of Sarah Water's novel reclaim the essence of desire

Sarah Waters’s Fingersmith and Park Chan-wook’s film adaptation, The Handmaiden, masterfully intertwine themes of betrayal, liberation, and the redemptive power of intimacy, all while drawing sharp distinctions between pornography and erotic love.

The Intricate Worlds of Fingersmith and The Handmaiden

Set in Victorian England, Fingersmith is a dark, atmospheric tale where orphan Susan “Sue” Trinder becomes entangled in a con designed by the charismatic conman Gentleman. Sue is tasked with aiding his scheme to seduce a wealthy heiress, Maud Lilly, so Gentleman can seize her fortune. Yet, as Sue grows closer to Maud, her own loyalties falter, and unexpected intimacy begins to bloom. The novel unravels a tapestry of secrets, revealing that both women have been manipulated in ways neither fully comprehends.

Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden transposes this story to 1930s Korea under Japanese colonial rule. By shifting the setting, Park adds layers of cultural and historical tension to the original plot. The film follows Sook-hee, a pickpocket recruited to help a conman posing as a Japanese count in his plan to defraud Lady Hideko, an heiress trapped in her uncle’s oppressive grip. Like *Fingersmith*, the film delivers a series of shocking twists, but its lush cinematography and explicit sensuality create a distinctly different tone.

Both stories offer a gripping dance between betrayal and trust, but while Fingersmith leans on psychological suspense, The Handmaiden revels in visual opulence, blending graphic eroticism with a sharp critique of patriarchal control.

Love as a Refuge from Pornography

A key theme in both works is the distinction between exploitative, dehumanizing pornography and the redemptive nature of true erotic love.

As Peter Bradshaw observes in The Guardian, The Handmaiden portrays sex as “the sanctuary from pornography... the refuge from porn and its furniture of abuse and control.”

Pornography and Control in Fingersmith

In Fingersmith, Maud Lilly is forced to perform readings of pornographic material for male audiences under the control of her sinister uncle. These moments are mechanical and degrading, underscoring how her identity is reduced to an object for male consumption. Against this backdrop, her relationship with Sue is a radical departure—a tender and subversive act that reclaims intimacy as a space for mutual trust and desire.

Their love is a rebellion against the commodification of Maud’s body and identity. Through their connection, Waters contrasts the lifeless, voyeuristic nature of pornography with the vibrant authenticity of reciprocal passion.

Reclaiming Desire in The Handmaiden

Park Chan-wook’s adaptation takes this contrast further. Lady Hideko’s life is steeped in the grotesque trappings of her uncle’s pornographic enterprise, where she is groomed and coerced into performing erotic readings. The cold, clinical atmosphere of these scenes highlights the oppressive nature of her imprisonment, with the uncle’s mansion serving as a metaphorical and physical prison.

In sharp contrast, Hideko’s love scenes with Sook-hee are intimate, unrestrained, and deeply personal. The cinematography lingers on their mutual pleasure and emotional vulnerability, emphasizing an authentic bond that exists outside the gaze of male control. Sex becomes their sanctuary—a way to reclaim their bodies and desires from a world intent on exploiting them.

Liberation Through Erotic Love

Both Fingersmith and The Handmaiden critique systems that commodify and control women’s sexuality. Pornography, in these narratives, symbolizes the dehumanizing forces of patriarchal oppression. In contrast, the love between the protagonists offers a vision of intimacy as liberation. It becomes an act of defiance, reclaiming the sanctity of connection from a world that seeks to diminish it.

In both works, love is not merely a refuge but a revolution. By positioning intimacy as a deeply humanizing force, these stories challenge us to reconsider the power dynamics that shape our understanding of desire.

Both works might differ in tone, setting, and style, but they share a profound commitment to exploring love’s transformative power. Whether through the foggy streets of Victorian England or the lush, oppressive estates of colonial Korea, both narratives remind us of the resilience found in intimacy—and the courage it takes to reclaim one’s identity in the face of exploitation.

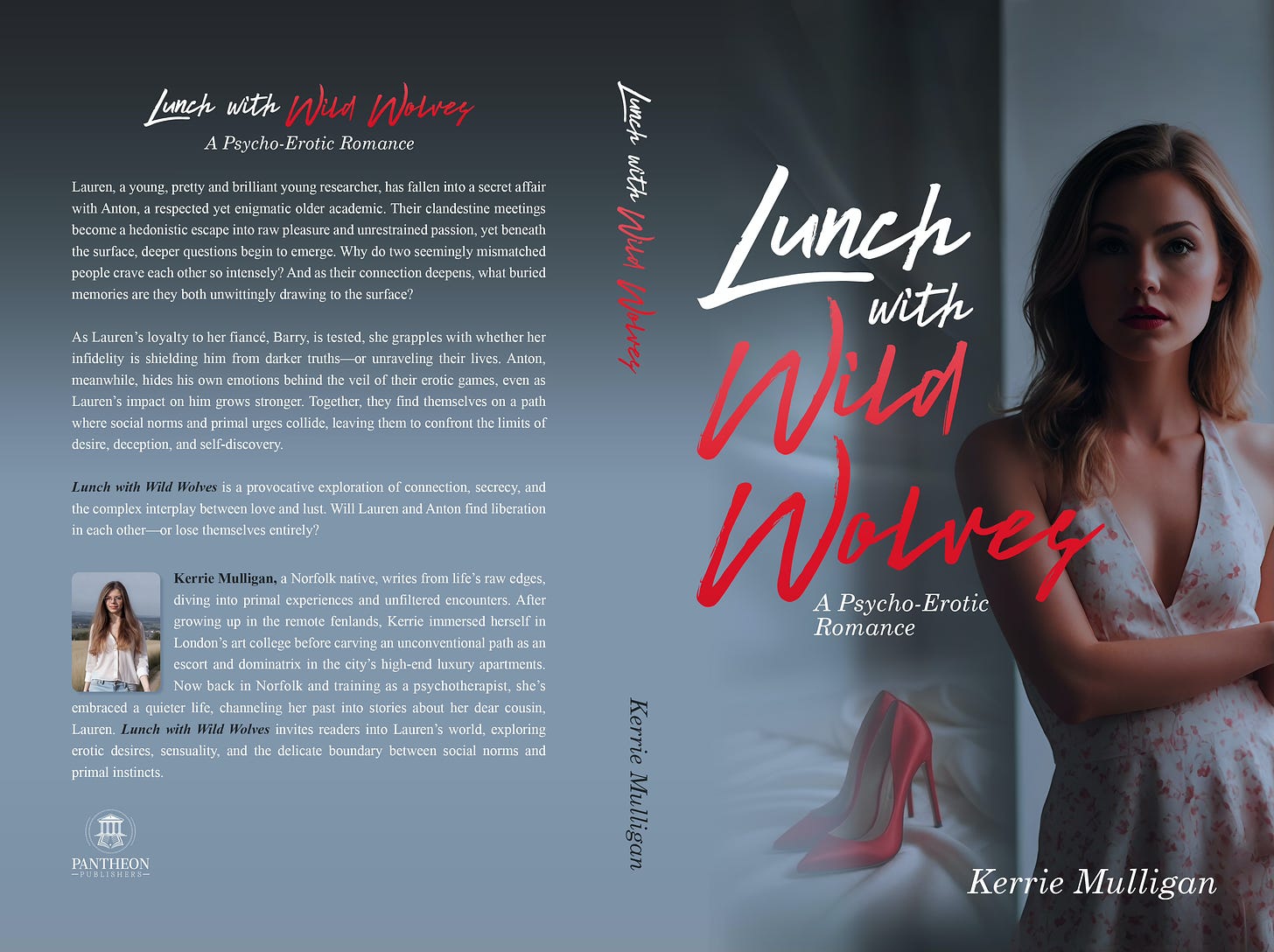

My first novel is out in December! Subscribe for early extracts and discounts £££